Local Residents Return From Delegation Trip With New Views On Immigration

- OLA of Eastern Long Island

- Aug 8, 2016

- 6 min read

Updated: May 1, 2022

By Jon Winkler and Kelly Zegers

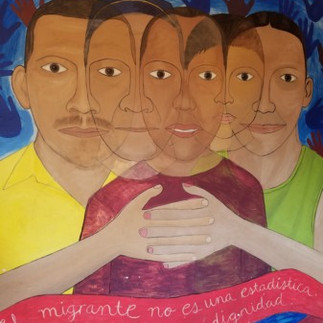

This past July—as the issue of immigration has been at the forefront of America’s national discussion—a group of volunteers traveled south of the U.S.-Mexico border to see how the poorest Mexican and Central American families live, and returned with a new outlook.

Fourteen Long Island residents spent 10 days in Oaxaca, the second poorest state in Mexico, from July 9 to July 18 to learn about the working conditions the locals face and the impact the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, has had on their livelihoods. The delegates learned many of the reasons residents there and migrants from Central America give for wanting to come to the United States in search of a better life.

“We weren’t there to go to another country and point out that country’s flaws,” said Minerva Perez, a Sag Harbor resident and the executive director of Organización Latino Americana of Eastern Long Island, known as OLA. “We were there to go to a country that has been directly impacted by many U.S. policies and take a look at what we can do as people from the United States and how we can view this as people from the United States.”

The trip was funded and organized by the Hagedorn Foundation, a nonprofit grant-making organization based in Roslyn that supports other organizations on Long Island that pursue social justice issues, immigration reform and civic engagement.

“We make a grant through a local immigration program to an organization called Witness For Peace,” said Sandra Dunn, the program director of the Hagedorn Foundation. “I’ve been making this grant to them since 2010. We usually take 10 to 15 people, go down to the capital city of Oaxaca, also called Oaxaca, and we learn about the root causes of migration. I’m always looking for people who are involved in their community and/or connected to an education network, like a classroom or a library. The point is to have those people come back and share what they’ve learned with their networks and communities.”

The Hagedorn Foundation was founded in 2005 with funds left to Amy Hagedorn when her husband, Horace Hagedorn, the man who helped market Miracle-Gro fertilizer into a multi-million dollar success, died. Mr. Hagedorn left his widow $60 million dollars to start the foundation that would help support Long Island organizations looking to make a difference.

Ms. Dunn said that Hagedorn is a “spend-down” organization, meaning the foundation would use all of its assets overtime instead of applying for more money. Because of this, Ms. Dunn said that Hagedorn will have spent its remaining funds by 2017 and will therefore close its doors permanently, which makes this recent delegation trip all the more significant.

“Part of our mission here at the Hagedorn Foundation is to ease people’s reactions to the truths of immigration,” Ms. Dunn said. “One way we do that is by educating local Long Island residents about immigration. This trip is meant to educate Long Islanders who may not have daily contact with immigrants. They may have different opinions on immigration, but this is a way of immersing them in a place in Mexico that has had a lot of out-migration to other parts of Mexico and the U.S. to learn what the root causes of migration are. Beyond that, I think when people are dealing with facts and first-hand experience, they are better able to educate others and inject facts into the debate to create more understanding of the issue and to make Long Island a more welcoming place.”

Takeaways

In addition to Ms. Perez, two other residents from the East End were a part of the delegation, Leah Oppenheimer, of Sag Harbor, a social worker at the Children’s Museum of the East End in Bridgehampton, and Lisa Votino-Tarrant, a resident of the Shinnecock Indian Reservation and an administrative assistant at Wuneechanunk Shinecock Pre-school.

The delegation spent time meeting with families and non-governmental organizations to learn about the issues. One day, they learned about the effects of border control by meeting with families who had not seen loved ones for years at a time after they crossed the border into the United States, recalled Ms. Votino-Tarrant, who said they sat with families in their homes and listened to their stories.

“Families were going longer with their loved ones being away. So what used to be every year, every two years, then became every seven years, every 10 years, every 13 years, because it was just that much harder to get across the border at that point, and certainly much more dangerous,” Ms. Votino-Tarrant said.

Ms. Perez said the group met a woman who had not seen her husband in 15 years after he went to the United States to work, only to find out that he had been killed in a car accident without further explanation as to why or how it happened.

She said that, here in the United States, she meets the migrants who are trying to do the best for their families. But in Oaxaca, “I was meeting with people who were left.”

The hardest day for Ms. Votino-Tarrant was a visit to a migrant shelter in Oaxaca, filled mostly with people from Central American countries hoping to escape violence in their hometowns. There, migrants are allowed to stay three days as they make their way to the border.

The group met 18 men who openly shared their stories. One man had walked for 13 days from El Salvador to get to the shelter and arrived just the day before.

Another, a 19-year-old named Rudy who was working to return to the United States, told Ms. Votino-Tarrant he fell in love with the country and built a great passion for music, something he was able to show when he performed at the Rose Bowl.

“They wanted to know: Would they be safe? And we didn’t have really good answers for them. And it was hard, it was really hard,” Ms. Votino-Tarrant said.

She bonded with the men about soccer teams. “It was just like a normal conversation that you would have with anyone. But you know that no matter what, migrants face violence at some point along their journey. And if they haven’t faced it yet, they will.”

For Ms. Perez, a major takeaway was recognizing how trade policies, such as NAFTA, have played a role in hardships that make life difficult for people in Mexico, and as a result lead to migration north.

“The scales are so far tipped,” she said of inequalities between the local farmers and big companies that import goods into Mexico.

Also through NAFTA, silver and gold mountaintop mining by transnational companies has decimated farmland and divided communities as locals get jobs with those companies. Ms. Perez recalled meeting a woman who was working to defend the land that was being encroached by mining.

The woman was only about 26 years old, but the look in her eyes made her seem older, about 45 years old, Ms. Perez said. “She had been through so much. She had been shot in the leg. Her fellow leader in this fight against this mine happening was killed.”

The woman walked with a cane and spoke quietly.

“It was just almost chilling. You're leaning in to hear what they're saying and to grasp this fearsome, quiet, power that they have,” Ms. Perez said. “Her life is in danger, but she's meeting with us and telling us about this, and that was tremendously moving.”

One couple the delegation met stood out to Ms. Oppenheimer: The couple had returned to their home village to teach sustainable agriculture techniques, including how to grow crops without pesticides, which are difficult for farmers to afford.

“They are people who are educated and have chosen to go back and make their home villages better,” she said. “It was very moving.”

Teaching A Lesson At Home

Each of the women have thought of how they can apply their delegation experience to their lives and work now that they are back home on Long Island.

Ms. Votino-Tarrant said she wants to share what she has learned, perhaps through presentations at East End libraries.

“Basically just trying to share the information that I learned any way I can, even in just normal conversations I have with people,” she said, especially when someone might bring up a misconception about immigrants.

In terms of OLA, which focuses on arts, education and advocacy, the experience will help color choices for its annual film festival in November.

Ms. Oppenheimer, who teaches literacy at the Children’s Museum of the East End, will take what she learned to her work. While on the trip, she noticed how children in Oaxaca did not have easy access to books.

“Kids’ books in Oaxaca, Mexico, cost more than what people make in several weeks,” she learned. There was a library, she said, but it never appeared to be open whenever she passed by.

Seeing that has inspired her to start looking into how she can make sure that new immigrants become socialized into the culture of libraries and books, so that children can learn.

Comments